Building Your First Distributed Application With Ray Core¶

Having learned the fundamentals of the Ray API, we will now use it to create a more practical project. By the end of this chapter, you will have created a reinforcement learning problem from scratch, implemented an algorithm to solve it, and used Ray tasks and actors to parallelize the solution across a local cluster, all within 250 lines of code.

This chapter aims to assist readers who are new to reinforcement learning. We will work through a simple problem and learn the necessary skills to solve it through hands-on practice. Advanced topics and terminology related to reinforcement learning will not be covered in this chapter, as Chapter 4 is dedicated to those subjects. However, even those who are more experienced with reinforcement learning may find value in implementing a traditional algorithm in a distributed environment.

The current chapter is focused on using Ray Core exclusively. It is hoped that the reader will come to understand the versatility and efficiency of Ray Core, particularly in regards to conducting distributed experiments that would otherwise require a significant amount of effort to set up. However, before moving on to implementation, it is worth briefly discussing the concept of reinforcement learning in greater detail. If you have prior experience with RL, feel free to skip this section.

You can run this notebook directly in

Colab.

In any case, make sure you have Ray installed first:

! pip install "ray==2.2.0"

Introducing Reinforcement Learning¶

There is an app on my phone that is one of my favorites because it is able to accurately identify and label different plants in my garden just by being shown a picture of the plant. This is very useful for me because I am not good at telling them apart. In recent years, there have been a lot of impressive apps like this one that have been developed.

Ultimately, the aim of AI is to create intelligent agents that are capable of much more than just classifying objects. Imagine an AI application that not only recognizes your plants, but is also able to take care of them. In order to do this, the AI would need to be able to:

- Function in dynamic environments, such as changes in seasons

- React to changes in the environment, like severe weather or pests affecting the plants

- Take a series of actions, such as watering and fertilizing the plants

- Achieve long-term goals, such as prioritizing the health of the plants.

An AI that observes its environment would be able to learn to explore possible actions and improve its solutions over time. For instance, it could be used for managing and optimizing a supply chain, restocking a warehouse based on fluctuating demand, or coordinating the processing steps in an assembly line. The "Coffee Test" proposed by Stephen Wozniak is another example of what an AI could be capable of - finding and using a coffee machine and all necessary ingredients to brew a cup of coffee, although it may not be able to sit down and enjoy it. Can you think of any other examples that fit these criteria?

The above requirements can be understood as part of a machine learning subfield called reinforcement learning (RL). RL involves agents interacting with their environment by observing it and taking actions. In RL, agents evaluate their environment by assigning a reward value to certain outcomes (e.g., the health of a plant on a linear scale). The term "reinforcement" refers to the idea that agents will hopefully learn to engage in behaviors that lead to desirable outcomes (high reward) and avoid negative or punishing situations (low or negative reward).

To better understand how agents interact with their environment, it is common to create a computer simulation of it. However, it is not always possible to do so. To provide an example of this in practice, we will build a simulation where agents interact with their environment together.

Setting Up a Simple Maze Problem¶

The app we are developing consists of a 2D maze game in which a single player can move in four directions. The maze is set up as a 5x5 grid, with one of the 25 cells being the "goal" that the player, called the "seeker," must reach. Instead of providing a pre-determined solution, we will use a reinforcement learning algorithm so that the seeker can learn how to find the goal through repeated simulations of the maze. The seeker will be rewarded for reaching the goal and the algorithm will track which decisions were successful and which were not. To make the process more efficient, we will use the Ray API to parallelize both the simulations and the training of the RL algorithm.

We will continue to use local clusters for now, rather than deploying the application on an actual Ray cluster made up of multiple nodes. If you want to learn about setting up Ray clusters and are interested in infrastructure topics, you can skip ahead to Chapter 9. However, make sure you have Ray installed by running the command pip install ray.

We will begin by creating the 2D maze that we previously discussed. This involves creating a 5x5 grid in Python, which starts at (0, 0) and ends at (4, 4). We need to also define how the player can move around the grid. To do this, we will use a class called Discrete to represent the four cardinal directions of movement: up, down, left, and right. This class will allow us to move in multiple directions, rather than just four. Don't worry, we will need this generalized Discrete class later on in the process.

import random

class Discrete:

def __init__(self, num_actions: int):

""" Discrete action space for num_actions.

Discrete(4) can be used as encoding moving in

one of the cardinal directions.

"""

self.n = num_actions

def sample(self):

return random.randint(0, self.n - 1)

space = Discrete(4)

print(space.sample())

Sampling from a Discrete(4) distribution will randomly generate one of the numbers 0, 1, 2, or 3. These numbers can be interpreted in any way we choose, such as representing the directions "down," "left," "right," and "up," respectively. In order to create a maze and set the position of the player and the goal, we will create a Python class called Environment. This class will be named "Environment" because the maze serves as the environment in which the player exists. To make things easier, we will always place the player at the coordinates (0, 0) and the goal at (4, 4). In order to make the player move and attempt to reach the goal, we will initialize the Environment with an action space of Discrete(4).

To complete the setup for our maze environment, we need to encode the seeker's position as a Discrete(5*5). This will allow us to later implement an algorithm that keeps track of which actions lead to successful outcomes for different seeker positions. In reinforcement learning terminology, the information that is accessible to the player is known as an observation. Similarly, we can define an observation space for the seeker. The following code demonstrates this concept:

import os

class Environment:

def __init__(self, *args, **kwargs):

self.seeker, self.goal = (0, 0), (4, 4)

self.info = {'seeker': self.seeker, 'goal': self.goal}

self.action_space = Discrete(4)

self.observation_space = Discrete(5*5)

def reset(self):

"""Reset seeker position and return observations."""

self.seeker = (0, 0)

return self.get_observation()

def get_observation(self):

"""Encode the seeker position as integer"""

return 5 * self.seeker[0] + self.seeker[1]

def get_reward(self):

"""Reward finding the goal"""

return 1 if self.seeker == self.goal else 0

def is_done(self):

"""We're done if we found the goal"""

return self.seeker == self.goal

def step(self, action):

"""Take a step in a direction and return all available information."""

if action == 0: # move down

self.seeker = (min(self.seeker[0] + 1, 4), self.seeker[1])

elif action == 1: # move left

self.seeker = (self.seeker[0], max(self.seeker[1] - 1, 0))

elif action == 2: # move up

self.seeker = (max(self.seeker[0] - 1, 0), self.seeker[1])

elif action == 3: # move right

self.seeker = (self.seeker[0], min(self.seeker[1] + 1, 4))

else:

raise ValueError("Invalid action")

obs = self.get_observation()

rew = self.get_reward()

done = self.is_done()

return obs, rew, done, self.info

def render(self, *args, **kwargs):

"""We override this method here so clear the output in Jupyter notebooks.

The previous implementation works well in the terminal, but does not clear

the screen in interactive environments.

"""

os.system('cls' if os.name == 'nt' else 'clear')

try:

from IPython.display import clear_output

clear_output(wait=True)

except Exception:

pass

grid = [['| ' for _ in range(5)] + ["|\n"] for _ in range(5)]

grid[self.goal[0]][self.goal[1]] = '|G'

grid[self.seeker[0]][self.seeker[1]] = '|S'

print(''.join([''.join(grid_row) for grid_row in grid]))

We have finished building the Environment class that is used in our 2D-maze game. This class allows us to move through the game, determine when it has ended, and reset it. The player, referred to as the seeker, can also view the game's environment and receive rewards for reaching the goal. Now, we can use this implementation to play a game of finding the goal using a seeker that randomly selects actions by creating a new Environment, applying actions to it, and displaying the environment until the game ends.

import time

environment = Environment()

while not environment.is_done():

random_action = environment.action_space.sample()

environment.step(random_action)

time.sleep(0.1)

environment.render()

If you run the program on your computer, you will eventually see that the seeker has found the goal and the game is over. It may take some time if you are unlucky. While you may argue that this is a very simple problem that can be solved by simply taking 8 steps (4 right and 4 down in any order), the purpose of using machine learning in this situation is to be able to tackle more difficult problems in the future. The idea is to create an algorithm that can figure out how to play the game on its own by observing the game, making decisions about what to do next, and receiving rewards for its actions.

If you are interested in doing so, now is an appropriate time to make the game more complex on your own. As long as you do not alter the interface established for the Environment class, you have the option to modify the game in numerous ways. Here are a few ideas:

- Make the grid a 10x10 size or randomly determine the initial position of the seeker.

- Make the outer walls of the grid hazardous. If you try to touch them, you will receive a penalty of -100.

- Add obstacles in the grid that the seeker cannot pass through.

If you are feeling particularly adventurous, you could also randomly determine the goal position. However, be mindful that the seeker currently has no information about the goal position through the get_observation method. You may want to consider tackling this last exercise after you have completed reading this chapter.

Building a Simulation¶

Now that the Environment class has been implemented, what is required to help the seeker learn how to play the game effectively? How can it consistently find the goal in the minimum required number of eight steps? To assist with this, we have provided the maze environment with reward information so that the seeker can use this to learn how to play the game. In reinforcement learning, the player repeatedly plays the game and learns from their experiences. The player is often referred to as an agent that takes actions in the environment, observes its state, and receives a reward. The better the agent learns, the better it becomes at interpreting the current game state and finding actions that lead to more rewarding outcomes.

In order to use any reinforcement learning algorithm, it is necessary to have a way to simulate the game repeatedly in order to gather experience data. Therefore, we will be creating a simple Simulation class soon. Additionally, we need the concept of a Policy, which is a way to determine the actions to take in a game. Currently, the only option we have is to randomly sample actions for our seeker. However, a Policy allows us to select better actions based on the current state of the game. A Policy is defined as a class with a get_action method that takes a game state and returns an action.

In our game, the seeker has 25 possible states on the grid and can take 4 actions. One strategy is to assign high values to state-action pairs that will result in a high reward and low values to those that will not. For example, moving down or right is usually a good choice, while moving left or up is not. We can create a 25x4 table of all possible state-action pairs and store it in our Policy. Then, when given a state, our policy can return the highest value for any action. While figuring out the best values for these pairs is a challenge, we can start by implementing this Policy and worry about finding a suitable algorithm later.

import numpy as np

class Policy:

def __init__(self, env):

"""A Policy suggests actions based on the current state.

We do this by tracking the value of each state-action pair.

"""

self.state_action_table = [

[0 for _ in range(env.action_space.n)]

for _ in range(env.observation_space.n)

]

self.action_space = env.action_space

def get_action(self, state, explore=True, epsilon=0.1):

"""Explore randomly or exploit the best value currently available."""

if explore and random.uniform(0, 1) < epsilon:

return self.action_space.sample()

return np.argmax(self.state_action_table[state])

I've included a small detail in the Policy definition that could potentially be confusing. The get_action method has an explore parameter. The purpose of this is to allow for exploration in situations where the current policy is not effective, such as when it always instructs the player to move left. In other words, sometimes it is necessary to try new approaches instead of relying solely on the current understanding of the game. As previously mentioned, we have not yet discussed how to improve the values in the state_action_table for the policy. For now, just keep in mind that the policy provides the actions to follow when playing the maze game.

The Simulation class is responsible for running a simulation of a game by taking in an Environment and following a given Policy until the goal is achieved and the game is completed. This process, known as a "rollout," generates a collection of observations and actions, which are referred to as the "experience" gained from the simulation. The Simulation class includes a rollout method that executes a full game and returns the resulting experience. The following code represents the implementation of the Simulation class:

class Simulation(object):

def __init__(self, env):

"""Simulates rollouts of an environment, given a policy to follow."""

self.env = env

def rollout(self, policy, render=False, explore=True, epsilon=0.1):

"""Returns experiences for a policy rollout."""

experiences = []

state = self.env.reset()

done = False

while not done:

action = policy.get_action(state, explore, epsilon)

next_state, reward, done, info = self.env.step(action)

experiences.append([state, action, reward, next_state])

state = next_state

if render:

time.sleep(0.05)

self.env.render()

return experiences

We will be using a specific algorithm to learn from the experiences we collect in a rollout, which are comprised of four values: the current state, the action taken, the reward received, and the next state. These values are necessary for our algorithm, but other algorithms may require different experience values. Although our policy has not yet learned anything, we can test its interface by creating a Simulation object, using the rollout method on the policy, and then printing out the state_action_table of it.

untrained_policy = Policy(environment)

sim = Simulation(environment)

exp = sim.rollout(untrained_policy, render=True, epsilon=1.0)

for row in untrained_policy.state_action_table:

print(row)

In order to accurately address the issue, both simulation and a policy were utilized. The only remaining task is to create a clever method for updating the policy's internal state based on the collected data so that it is able to effectively learn how to play the maze game.

Training a Reinforcement Learning Model¶

Suppose we have a set of experiences from a few games. How can we effectively update the values in the state_action_table of our Policy? One way to do this is by considering a specific situation, such as being at position (3,5) and deciding to go right, which brings us to position (4,5) just one step away from the goal. In this case, continuing to go right would result in a reward of 1, indicating that the current state (3,5) combined with the action of going right should have a high value. On the other hand, going left in the same situation does not lead to any reward, so the value of the state-action pair involving left movement should be low.

The expected reward from taking an action from the next state by consulting our state_action_table for the policy. This allows us to evaluate the potential benefits of taking a certain action after reaching the next state. Essentially, this is how we define an experience – by being in a specific state, taking an action that leads to a reward, and then transitioning to the next state.

{python}

next_max = np.max(policy.state_action_table[next_state])There are several ways to compare the knowledge of this value to the current state-action value, which is the value stored in the policy's state-action table for the given state and action. One option is to calculate a weighted sum of the old value and the expected value, using a formula such as new_value = 0.9 * value + 0.1 * next_max. The weights of 0.9 and 0.1 have been chosen to reflect the preference for keeping the old value, and the important factor is that the weights sum to 1. However, this approach does not take into account the important information from the reward, which should be given more trust than the projected next_max value. To account for this, it may be beneficial to discount the next_max value by 10%. The updated state-action value would then be calculated as follows:

{python}

new_value = 0.9 * value + 0.1 * (reward + 0.9 * next_max)If you have a lot of experience with reasoning like this, the previous paragraphs may be overwhelming. However, if you have understood the explanations until now, you will probably find the rest of this chapter easy to follow. Mathematically, this was the most difficult part of this example. If you have worked with RL before, you will have realized that this is an implementation of the Q-Learning algorithm. It is called this because the state-action table can be represented as a function Q(state, action) that returns values for these pairs.

We’re almost there, so let’s formalize this procedure by implementing an update_policy function for a policy and collected experiences:

def update_policy(policy, experiences, weight=0.1, discount_factor=0.9):

"""Updates a given policy with a list of (state, action, reward, state)

experiences."""

for state, action, reward, next_state in experiences:

next_max = np.max(policy.state_action_table[next_state])

value = policy.state_action_table[state][action]

new_value = (1 - weight) * value + weight * \

(reward + discount_factor * next_max)

policy.state_action_table[state][action] = new_value

With this we can easily define a function to train a policy as follows. The train_policy function follows the steps of initializing a policy and a simulation, running the simulation multiple times (in this case, 10000 times), collecting the experiences for each game through a rollout, and updating the policy using the update_policy function with the collected experiences.

def train_policy(env, num_episodes=10000, weight=0.1, discount_factor=0.9):

"""Training a policy by updating it with rollout experiences."""

policy = Policy(env)

sim = Simulation(env)

for _ in range(num_episodes):

experiences = sim.rollout(policy)

update_policy(policy, experiences, weight, discount_factor)

return policy

trained_policy = train_policy(environment)

In the field of RL, a full play-through of the maze game is referred to as an episode. That is why the train_policy function has an argument called num_episodes, rather than num_games. Now that we have a trained policy, we want to see how well it performs. Previously in this chapter, we ran random policies a couple of times to get an idea of their effectiveness in the maze problem. However, we now want to properly evaluate our trained policy over multiple games and see how it performs on average. Specifically, we will run our simulation for several episodes and measure the number of steps it takes to reach the goal in each episode. To do this, we will implement an evaluate_policy function that accomplishes this task.

def evaluate_policy(env, policy, num_episodes=10):

"""Evaluate a trained policy through rollouts."""

simulation = Simulation(env)

steps = 0

for _ in range(num_episodes):

experiences = simulation.rollout(policy, render=True, explore=False)

steps += len(experiences)

print(f"{steps / num_episodes} steps on average "

f"for a total of {num_episodes} episodes.")

return steps / num_episodes

evaluate_policy(environment, trained_policy)

To summarize, the policy that has been trained is capable of finding the best solutions for the maze game. This means that you have successfully implemented your first RL algorithm from scratch. Now, consider whether the evaluation function would still be effective if the seeker was placed in random starting positions. Try making the necessary adjustments to find out. Additionally, think about the assumptions that were made when designing the algorithm, such as the assumption that all state-action pairs can be listed. Would this algorithm still work effectively if there were millions of states and thousands of actions?

Building a Distributed Ray App¶

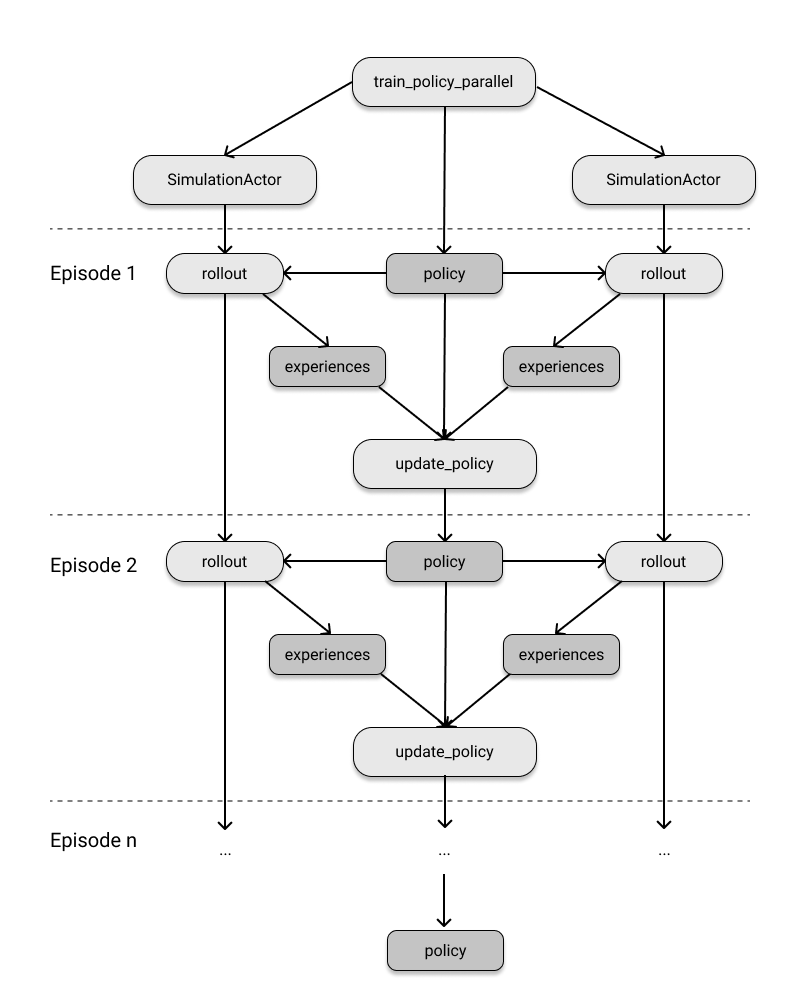

You might be wondering how this example relates to Ray. To turn this RL experiment into a distributed Ray application, we only need to write three code snippets. First, we will make the Simulation a Ray actor with a few lines of code. Next, we will define a parallel version of train_policy that is similar in structure to the original, but only parallelizes the rollouts, not the policy updates. Finally, we will train and evaluate the policy as before, but using the parallel version of train_policy.

The first step is to implement a Ray actor called SimulationActor:

import ray

ray.init()

@ray.remote

class SimulationActor(Simulation):

"""Ray actor for a Simulation."""

def __init__(self):

env = Environment()

super().__init__(env)

You should be able to understand the code presented in this section thanks to the knowledge of Ray Core that you gained in Chapter 2. While it may take some time to become comfortable with writing this type of code yourself, the concepts should be familiar to you. In the following example, we will demonstrate how to use a local Ray cluster to distribute the workload of reinforcement learning (RL) by creating a policy on the driver and four SimulationActor instances to perform distributed rollouts. We will store the policy in the object store with ray.put and pass it as an argument to the remote rollout calls to gather experiences over a specified number of training episodes. The finished rollouts will be retrieved with ray.wait, taking into account that some may finish before others, and the policy will be updated with the collected experiences. Finally, the trained policy will be returned.

def train_policy_parallel(env, num_episodes=1000, num_simulations=4):

"""Parallel policy training function."""

policy = Policy(env)

simulations = [SimulationActor.remote() for _ in range(num_simulations)]

policy_ref = ray.put(policy)

for _ in range(num_episodes):

experiences = [sim.rollout.remote(policy_ref) for sim in simulations]

while len(experiences) > 0:

finished, experiences = ray.wait(experiences)

for xp in ray.get(finished):

update_policy(policy, xp)

return policy

This allows us to take the last step and run the training procedure in parallel and then evaluate the resulting as before:

parallel_policy = train_policy_parallel(environment)

evaluate_policy(environment, parallel_policy)

The output of the two lines is the same as when we previously ran the single version of the RL training for the maze. It's helpful to compare train_policy_parallel and train_policy line by line because they have the same overall structure. All we had to do to parallelize the training process was to use the ray.remote decorator on a class appropriately and then make the correct remote calls. It's helpful to have some experience to do this correctly, but it's worth noting how little time we spent considering distributed computing and how much time we were able to focus on the actual application code. We didn't need to completely change our programming approach and were able to handle the problem in a natural way. This is what we want and Ray excels at providing this kind of flexibility.

To conclude, let's briefly look at the execution graph of the Ray application we just created, as shown in the following figure.